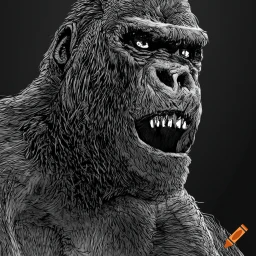

This essay examines the design and performance of the title character of King Kong in Peter Jackson’s 2005 remake, as well as their decision to expose their behind-the-scenes work in publicity material, online production diaries, and DVD special features. I argue that these ancillary materials do more than just promote the film; they also introduce discourses of realism and authenticity that influence how viewers respond to and judge the value of the film. While examinations of the publicity for the 1933 and 1976 versions of King Kong reveal that deception was deemed necessary to protect the fantasy created onscreen, the publicity for the latest version of the film shows that contemporary filmmakers do not feel the need to hide the apparatus so as not to ruin the illusion. Rather, it is only by breaking with older notions of realism that sought to keep the production apparatus invisible that Jackson and his team were able to frame motion capture in terms of authenticity and reference to the real world. To make audiences more comfortable with the relatively new technologies of computer-generated imagery and motion capture, however, the discourse of authenticity evoked by Jackson and Kong portrayer Andy Serkis still relies on notions of character psychology, Method acting, and the filmic record that hark back to the traditional values and uses of “old” media like (celluloid) film, photography, and theater. In particular, I consider motion capture to be an example of “digital indexicality,” a blend of computer-generated images and material recorded from reality. Motion capture demonstrates that indexicality persists in the digital age. Instead of positing a break between celluloid index and digital icon, motion capture prompts us to reevaluate the continuities between “old” and “new” media, investigating both as fusions of historical record and visual illusions.

“More than a Man in a Monkey Suit: Andy Serkis, Motion Capture, and Digital Realism,” Quarterly Review of Film and Video 28.4 (July 2011): 325–341.